What's Next at Cabrinha: Pat Goodman on Aluula and Bar Design | Part 2

In Part 1 of our interview with Pat Goodman, Pat compared Cabrinha's kite lineup, breaking down the Drifter, Switchblade, Nitro, and Moto X, and what each design is really built to do on the water. From wave riding to big air to all-around performance, he shared how Cabrinha approaches design and why having the right tool for the job still matters.

In Part 2, Brazilian Brother Rubens shifts the focus to design. Pat dives into advanced topics like Aluula and other high-end materials, the evolving role of design versus fabric choice, and the often-debated differences between low-V and high-V bar setups. It's a more technical discussion, but still grounded in real-world riding and offering a behind-the-scenes look at how today's kites are being refined and where design may be headed next.

Aluula: Performance, Tradeoffs, and Where It Fits

Rubens: I'd love to hear your thoughts on Aluula as a material. Do you see it as something that's here to stay? And how does it fit into the Moto X Design Works platform?

Pat: Aluula is incredibly stiff, but it also has a really snappy, lively feel that makes the kite extremely responsive. It's not just stable- it recovers very quickly when you steer, which gives it a unique performance character. That stiffness allows for reduced leading edge diameters, which changes the aerodynamics and significantly reduces overall weight. The material itself is already much lighter, around 80 grams per square meter versus roughly 140 for conventional fabrics, and when you can reduce spar and bladder sizes, you save even more weight. The bladder is actually one of the heaviest components in a kite.

That weight reduction opens the door for a three-strut kite to handle wind conditions that would normally require a five-strut kite. That was really the goal: to create a high-end big air kite that's noticeably lighter, faster, and more responsive in steering than something like the Nitro.

There's definitely a place for Aluula, especially in larger kite sizes. It's incredible material. But it's also very expensive, over six times the cost of traditional Dacron, and it doesn't have the longest lifespan. It requires more care. That said, when you ride it, you immediately feel the "wow" factor. It's a completely different experience compared to something like a Moto X Lite or a standard Design Works kite. It's like the difference between a Formula 1 car and a sporty BMW. Both are great, but one is a full-on race machine.

Do You Really Need Aluula to Compete?

When Aluula first came onto the scene, there was this idea that if you didn't have an Aluula kite, you couldn't compete at the highest level. I'm not convinced that's true anymore. We're now seeing riders on tour winning or at least performing just as well on non-Aluula kites. When that started happening, the narrative began to shift.

Aluula still absolutely has its place, but the urgency around it has quieted down. Some brands are still going all-in on it, but if you look closely at the tour today, plenty of riders are on kites without Aluula and doing just fine.

There's also the argument that because of the stiffness, Aluula gives you a larger usable wind range, so you can potentially own fewer kites. There's some truth to that, but it's a balance of cost, durability, and performance.

Innovation Beyond Aluula and the Evolution of Big Air

Rubens: I think that's where things like Brainchild come in. It feels like a clear statement of, "We're not doing Aluula; we're going to do something else." And it challenges the idea that you need Aluula to win competitions. What excites me is how many high-end material options there are now. For a while, it felt like things stagnated, especially when people were riding C-shaped kites for big air, which never made much sense to me given their limited depower and wind range.

Then you had that shift, first with the Pivot and Kevin Langeree going bigger than anyone else, and later with the Orbit, suddenly everything changed. Those kites made big air accessible to the average weekend rider.

Pat: And it's important to remember that those riders were winning on stock production kites. There was nothing custom about them, just kites you could pull straight out of the bag.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Big Air and the Industry

Rubens: Exactly. That accessibility is huge. I love where the industry is right now. There's so much excitement around big air, and it feels like that's clearly where the focus is heading. You still have die-hard unhooked freestyle riders, of course, but when I look at the kids riding here in Prea, they're not even thinking about unhooking. They want to go as big as possible.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on where you see the industry going next, not just for Cabrinha, but for kiteboarding as a whole, and how Cabrinha fits into that future.

Pat: Big air has really come full circle. At the beginning, that was the whole reason most of us got into this sport: just sending it and flying. I still remember the first time I saw someone really jump on a kite. I actually felt it in my stomach. I was windsurfing at the time, where a big jump was maybe three meters, and these guys were casually going ten meters without even trying. It was mind-blowing.

Material evolution has obviously played a huge role in that progression, Aluula being a big recent example, but at the end of the day, good design matters more than anything. If you look at what Ralf has done with Brainchild, it proves that a strong design can outweigh the material itself. A great designer can make something work even when the material isn't ideal.

I learned that lesson firsthand. There were times when I was constantly pushing NeilPryde to use better Dacrons because we were working with fabrics from Teijin that had a lot of elongation and were really difficult to design around. But the response I got was always, "This will make you a better designer." And he was right.

If you can make a kite fly well and perform using a material with limitations, you learn far more about how fabrics behave. It's easy when everything is stiff and low-elongation because you don't have to think as much. But when you're forced to overcome challenges, you gain a much deeper understanding of design. A good designer can make almost anything work.

That said, you're always going to get a different response and reaction from something like Aluula compared to conventional Dacron. But there's still a lot of room for improvement in materials, and there's already been massive progress over the last ten years.

The Push Beyond Aluula

Even the materials we use today in the Lite and Apex series are a result of that thinking. The Lite fabric, which is also used by several other brands, is something we helped develop years ago. We were frustrated with unbalanced fabrics that were essentially borrowed from the sailing dinghy world, so we pushed for a kite-specific inflated leading edge material.

The goal was a balanced weave with controlled elongation along the yarn columns, so the kite wouldn't deform as much. That meant less compensation in the design and cleaner-flying kites. That kind of progress doesn't always get talked about, but it's hugely important.

As for welded seam technology... I'm not completely sold. It's still sewn, just reinforced with welding, and there are often multiple rows of stitching anyway. It does make for a stiffer seam, and there may be something there, but it's not the silver bullet some people make it out to be.

What is happening, though, is that material manufacturers want a piece of the Aluula performance story, just without the $30-per-square-meter price tag. Conventional Dacron is more like $5 or $6 per linear meter, so the difference is massive. Aluula also requires more reinforcement and is more expensive to construct overall.

A lot of companies are now experimenting with Aluula alternatives. None of them have fully matched it yet, but some are starting to show real promise. North, for example, has been very active because they have their own material facilities. We were already experimenting heavily when I was there.

Across the industry, there's also a lot of work happening with hybrid Dyneema-polyester fabrics, with and without film. There's still plenty of room for growth.

Design, Software, and the Next Phase of Evolution

Design and materials evolve together, and software plays a huge role in that. Early on, when we were developing bow kites, the software literally couldn't draw them. The amount of sweep broke all the existing rules. That had to change.

Now, the design tools are incredibly powerful. I work closely with the software developer and use almost every tool available, to the point where he sends me beta versions because I tend to find the edge cases he missed. That said, more tools aren't always better. Sometimes too much information can actually get in the way.

We probably won't see massive breakthroughs every year. Big moments like the bow kite, and more recently Aluula, don't come around often. What's happening now is that designs have caught up. The performance gap between Aluula and non-Aluula kites isn't as big as it once was because designers have been forced to push harder.

Cabrinha's Focus Moving Forward

Rubens: I think that's true. After Aluula, a lot of designers, Kyle at F-One included, were racing to achieve that level of performance without using Aluula. Shifting gears a bit, I wanted to talk about Cabrinha's future. After your sabbatical, John and his partners were very intentional about bringing you back as head designer to put Cabrinha back on an innovation-focused path. Where do you see Cabrinha heading over the next few years?

Pat: Cabrinha is definitely going through a period of refinement. We're streamlining the product lineup, reducing SKUs, and making things more manageable for shops. There's no point in offering everything everyone else does just for the sake of it.

We want to focus on what we do best. Big air is obviously where the sport's attention is right now, and that area needs continued evolution, but you can't ignore other categories. Take the Moto XL or the Contra. There are places where 15 knots is considered windy, and those kites are the last man standing. When everyone else is walking up the beach, those riders are still out there, and with incredible hangtime because the wing loading is so light.

We're also moving away from the idea of offering the same kite in multiple materials just to cover every angle. If there's one version that's clearly the best, why dilute it? If we need a more affordable option, it makes more sense to design a different kite that's cheaper to manufacture rather than splitting the same design into multiple material tiers.

Cabrinha will always focus on evolution, but it happens in steps. Things do get better year over year, just not with a massive "big bang" every single season.

Low-V vs. High-V: What's Really Going On?

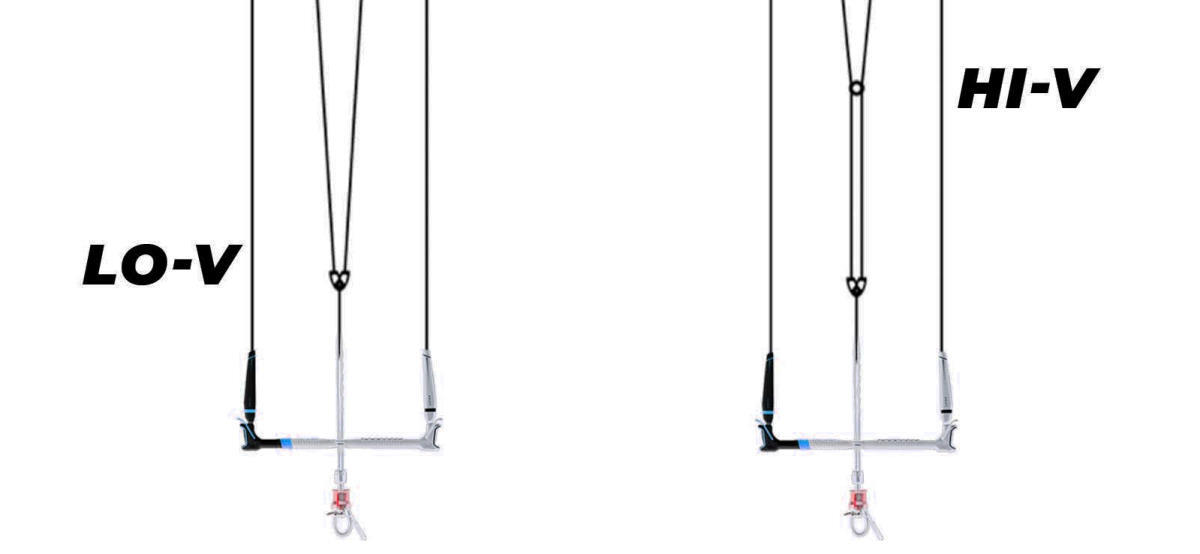

Rubens: One thing I've always found interesting about Cabrinha is that every kite is designed around a low-V bar, whereas other brands, Ralf's designs, for example, lean heavily toward a high-V platform. Can you talk about the design differences between low-V and high-V, the tradeoffs involved, and whether there's ever a case where a high-V setup actually makes more sense?

Pat: This is actually a pretty heated topic internally right now. With big air kites, if you're trying to squeeze out that last bit of improvement, especially tightening the loop radius, it's really hard to do without a high-V. The high-V pulls the wingtips in, which allows the faster side of the kite to reach higher airspeeds and come around quicker.

It's similar to shortening your control lines. Everyone knows how much faster a kite feels on shorter lines, and a high-V gives you some of that effect without actually shortening the lines.

Of course, there are downsides. From a teaching or school perspective, if the kite does a somersault, you can't untwist crossed lines in the water with a high-V. It also reduces power delivery for a couple of reasons. As you raise the V, you're effectively shortening the front lines, similar to pulling trim, and the wingtips fly at a slightly lower angle of attack, which produces less power.

So yes, you feel right away that the kite has less grunt. There are definitely pros and cons.

I've tested everything: 30 cm, 1 m, 2 m, all the way up to 10 m. We actually used high-V for a long time. All the old IDS systems were around a 3-meter high-V.

It's funny — a few years ago I borrowed a kite from a friend who was riding it on an old IDS bar. I took it out and immediately thought, "Wow, this thing is fast." I'd been riding low-V for so long that it really surprised me.

That's why I've been testing everything on both setups. The new bar we have coming includes an optional ring that lets you run a 6-meter high-V. It doesn't come installed, because our current kites were developed around low-V, but it's very easy to add or remove- it takes about two seconds.

Some kites absolutely love high-V. Others really don't.

John and I go back and forth on this all the time — he's not a high-V guy at all. I'm completely convinced that if you're serious about megaloops, high-V helps. The kite comes around faster, recovers better, and gives you more pivoty steering. That tighter loop is critical when you're trying to get the kite around without being dragged too far downwind.

Brands like Duotone and Brainchild have been developing on high-V for decades, and those kites generally don't feel great on low-V. Since I've been back, we've started testing everything both ways, and I'm finding that high-V lets me push the big air kite to the next level in terms of looping performance.

I really believe the day will come when we offer kites that we recommend flying on high-V; just like rear bridle settings, it's about giving riders options. Feeling is half of performance in this sport, and everyone has their own preference.

Still Testing, Still Learning

Rubens: This is awesome. It's honestly inspiring to see someone with your experience still so excited to test, learn, and question things. I think that enthusiasm really comes through in this conversation, and people are going to get a lot out of it. Thank you so much for your time and for being so open with us.

Pat: Thanks for having me. I really appreciate the chance to talk, and I'm looking forward to coming down to visit sometime soon.

MACkite Subscription Links:

YouTube | Instagram | Spotify Oddcasts

Contact MACkite Below:

800.622.4655 | Kiteboarder@MACkite.com | LIVE Chat Messenger

Recent Posts

-

Why the Ride Engine Empax Vest Is a Shop Favorite

When riders ask us about flotation, the first thing we usually have to do is slow the conversation …26th Feb 2026 -

2026 Duotone Twintip Range: What's New, and Which Board Is Right for You?

The 2026 Duotone twintip lineup has officially landed, and it's refined, more responsive, and purp …25th Feb 2026 -

Naish Hatch Parawing | Upwind Power, Broad Range, and Smart Price

The Naish Hatch is Naish’s performance-driven entry into the evolving parawing category, positione …20th Feb 2026